Built environments surround us. They are everywhere: homes, offices and government buildings, gas stations, shopping malls, movie theaters, factories, apartment buildings, tree houses, igloos, and skyscrapers. There are even more built environments to consider when you include any human-made structure, such as boats, cars, trains, and aeroplanes. According to the University of Windsor, the term built environment is used “when referring to those surroundings created for humans, by humans, and to be used for human activity.”1 So, the list of built environments extends to bridges, parks, roads, paths and walkways, city squares, transportation systems, and even sidewalks.

Because built environments are everywhere, they have a powerful influence on our everyday lives. One of the most influential built environments is the early childhood classroom.

Importance of Early Childhood Built Environments

Humans spend an enormous amount of time in built environments. In 2001, the National Human Activity Pattern Survey2 revealed that humans spend an average of 86.9 percent of their time indoors. More recent studies show that people spend 90 percent of their day inside; no wonder we are labelled the “indoor generation”3. These dismal statistics include not only adults but also young children. The 2019 Digest of Educational Statistics4, for example, reported that children under the age of five who are in childcare centers spend an average of 30 hours a week in these built environments. With all of these statistics in mind, it is easy to understand why the indoor environments of early childhood classrooms are important, and how they have the power to either positively or negatively shape young children’s lives. When designing and building child care centers—and specifically learning spaces within the built environment—the primary focus is often on the four walls, appropriate square footage for the number of children occupying the space, where windows are placed, doors are located, number of bathrooms, and so on. Although focusing on these elements is important, there is much more to consider.

This article is asking you to refocus your perspective on designing early childhood environments and potentially develop a new approach: designing early childhood environments from a Brain-SET formula. Developed by Kathryn Murray5, this new design approach puts young children’s brains at the heart of classroom design.

Functionality: A Traditional Design Approach

The traditional way of thinking about designing early childhood environments is to focus on the layout in terms of the placement of learning centers. Early childhood educators typically organize their classrooms with some areas in mind. Examples include art, home living or dramatic play, blocks, writing, literacy, math, science, manipulatives, and gathering areas. Inclusion of these areas is based on children’s ages, developmental levels, interests, and possibly curriculum goals. Traditionally, our mindset for the classroom layout and design is functionality. Positioning the art center near a source of water and locating it on a tiled surface, for example, makes for easier clean-up. Placing the block center in a secluded corner helps avoid high foot traffic and reduces children’s skirmishes when their structures are knocked over. In addition to the traditional classroom layout, early childhood educators also carefully consider functionality when selecting appropriate and relevant learning materials to include in each learning space. These educational materials are displayed and positioned so children can be autonomous when finding, using, and returning materials6. Another strategy is ensuring the materials that are used together are placed together7. Paintbrushes, paper, and paint, for example, are clustered together near a paint surface.

While all this talk about designing a classroom based on functionality may sound familiar and seem right, there is a critical piece missing from our thinking. We are approaching classroom design from a myopic rather than holistic perspective. We are designing environments based on function, rather than on the development of young children’s brains.

Brain-SET: A New Design Approach

Today’s children are growing up in a fast-paced and sometimes chaotic world8. Technology, media, screen time, nature-deficit disorder, fast-paced days, constant visual and physical stimulation, and complicated lives take a toll on children. The classroom is no exception. Often, children’s complex worlds overflow into the classroom, resulting in a range of issues, such as inappropriate behaviors, inability to focus, inadequate communication skills, and a lack of self-regulation. There is little room for calm, yet a significant body of research indicates that children do not thrive in chaotic learning environments9. With all this in mind, it becomes evident that early childhood educators need to look beyond the tradition of functionality and begin to develop strategies for bringing calm into the classroom design.

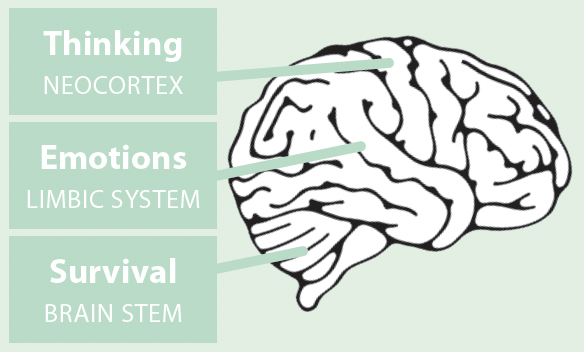

The Brain-SET formula is one solution for bringing calm into the learning space. This formula aligns classroom design with the child’s brain and is based on the three developmental levels of the brain: Survival, Emotion, and Thinking.

For children to thrive, these levels of the brain need to align and work in harmony with the classroom design. The Brain-SET formula incorporates three different design elements, which are critical for shaping children’s learning experiences:

1. Survival: Design for Learning

What happens in the brain. The survival (or reptilian) brain area sits at the base of the brain known as the brainstem, and its function is to make sure we survive. It controls our involuntary bodily functions, such as breathing and pumping of the heart10. Being and feeling safe work in tandem with each other, and this feeling of safety and security has to be in place before any thinking or learning can occur. If children are emotionally upset, the fight, flight, freeze response is activated. In turn, the production of the cortisol hormone in the brain increases. Over time, high levels of hormone saturation put the child on constant “high alert.” When this happens, executive functioning skills in the brain are affected. Children’s memories, abilities to adapt to new contexts, and self-regulation suffer as a result11.

Consequently, it is critical to help young children feel safe and secure in early childhood environments. To address the needs of the survival brain, creating a calm learning space may be the answer for the overstimulated or traumatized child.

What happens in calm classrooms. Helping young children to feel safe by calming the survival part of the brain is of high importance. One strategy for aligning the brain’s needs with classroom design is through the Design for Learning element of the Brain-SET formula. Research has shown that children experience an increased sense of safety when there are clear and visible pathways between spaces; rounded corners that soften the look and feel of the classroom; and, small defined spaces12. The survival-centered classroom should include such small spaces, which encourage children of all ability levels to engage in their own unique way. Most learning centers are designed to accommodate larger groups of children, rather than small areas for just a few children. Create a sense of calm by carving out several small spaces in the early childhood environment. Look around your classroom. Are there any unoccupied spaces that you could transform into a safe haven for a few children?

Small cozy spaces with different textures and fabrics help children to feel secure and calm. Photo by Kathryn Murray from Mudjimba Kindergarten.

Small cozy spaces with different textures and fabrics help children to feel secure and calm. Photo by Kathryn Murray from Mudjimba Kindergarten.

Small defined spaces for one or two that include sensory exploration and natural materials are open-ended and calming. Photo by Sandra Duncan.

Small defined spaces for one or two that include sensory exploration and natural materials are open-ended and calming. Photo by Sandra Duncan.

2. Emotions: Feelings for Learning

What happens in the brain. The limbic system (mammalian brain) and children’s emotions play a crucial role in children’s ability to form long-lasting memories. Episodic memories are memories strongly linked to emotion and are the easiest to recall. Semantic memories are more in line with facts and figures, with little connection to emotion, and are much harder to recall, especially in stressful situations. Use elements of emotion as a catalyst for learning by providing joyful experiences and opportunities to develop relationships. Reducing high-stress levels is important so that learning can occur as young brains mature.

What happens in calm classrooms. Memories are fueled by emotions; the stronger the emotion, the more vivid the memory. Activating the emotions area of the brain, therefore, is important for the storage of children’s long-term and short-term memories. This can be accomplished with the Feelings for Learning element of the Brain-SET formula. Emotion-centered learning spaces are inviting and welcoming. In a space designed for the mammalian brain, children feel both physically and emotionally comfortable. Emotion-centered learning spaces are specifically designed to create a sense of calm and physical ease. Design examples for emotion-centered environments include:

- Soft furnishings with cushioned couches, pillows, and throws

- A warm color palette that uses natural and relaxing colors

- Intimate and cozy spaces

- Multiple sources of natural and ambient light and limited overhead or fluorescent lights

- Elements of nature and natural objects with limited plastic

Environments that feel warm and home-like contribute to children’s emotional security. Using the learning spaces to promote calm and relaxed feelings opens up pathways to emotion-filled experiences.

Different spaces for thinking and learning. A small, cozy space can be as simple as baskets; small, defined spaces; wayfinding pathways; lowered roof line; and a fluffy cushion that promotes security and safety. Top photo is by Kelsey Shakelford and the bottom photo is by Sandra Duncan.

Different spaces for thinking and learning. A small, cozy space can be as simple as baskets; small, defined spaces; wayfinding pathways; lowered roof line; and a fluffy cushion that promotes security and safety. Top photo is by Kelsey Shakelford and the bottom photo is by Sandra Duncan.

Brain Development and Classroom Design |

|||

| Brain Area | Brain Focus | Design Elements | Design Strategies |

|

Survival Reptilian Brain Located in Brain Stem |

The Reptilian Brain sits at the base of the brain - this is the brainstem and is the first to develop in utero. It is designed for survival and controls involuntary responses to keep us alive and safe. |

Defined Spaces Wayfinding Lowered Ceiling Lines Acoustics Lighting Rounded Corners |

Design for learning Spaces are planned to provide experiences that help a child or small group of children to feel safe, secure and calm. |

|

Emotion Mammalian Brain Located in Limbic System |

The limbic system includes the amygdala, which governs emotions. The fight, flight, freeze responses are managed between the brainstem and the limbic system, to ensure survival. The limbic system is situated around the top of the ear. |

Soft Furnishings Soft Colors Psychological Containment and Security Soft Lighting Nature Connection |

Feelings for learning Cozy, small spaces with a natural feel are offered to ensure that children enjoy the sense of place or home, and are supported to build relationships. |

|

Thinking Human Brain Located in Neocortex |

The neocortex is the area of the brain used for thinking, memory, and problem-solving. It sits at the top of the brain and is linked to the two lower brains. |

Learning Spaces (Engagement) Recalibration Spaces (Respite) Meeting Spaces (Explicit Teaching) Proximity to others (Single or small group) Flexible Thinking Spaces (Seating Alternative) |

Spaces for learning A variety of spaces for different purposes are available for small groups, individuals, and class groups with flexible seating arrangements. |

3. Thinking: Spaces for Learning

What happens in the brain. The neocortex is where problem-solving, memory, thinking, and learning take place. The neocortex houses the brain’s executive functioning skills and includes working memory, mental flexibility, and self-control. The thinking part of the brain connects with the lower levels (emotion and survival) of the brain for a holistic approach to learning14. The thinking part of the brain requires stimulating, diverse, and interesting environments.

What happens in calm classrooms. Create thinking-centered environments by using the Spaces for Learning element of the Brain-SET formula. Thinking-centered classrooms require spaces of different sizes and shapes to enable the brain to be stimulated for learning. Examples of thinking-centered environments in calm learning spaces include recalibration spaces for respite and areas in which children can take a break from the larger group. Larger meeting spaces are required for explicit teaching, while proximity spaces cater to individuals, pairs, or small groups of children. The thinking brain functions best when the lower parts of the brain’s needs are met. Once children know that they are safe and secure and that their emotional needs are filled, the thinking brain has a chance to shine.

Next time you think about rearranging your space, rather than designing for functionality, consider using the Brain-SET formula. This formula—in concert with the three design strategies (Design for Learning, Feelings for Learning, and Spaces for Learning)—makes for calmer environments, calmer children, and calm brains. Remember, a calm brain is a thinking brain.

About the authors

|

Sandra Duncan, Ed.D., is working to assure the miracle and magic of childhood through indoor and outdoor classroom environments that are intentionally designed to connect young children to their classrooms, communities and neighborhoods. Duncan is an international consultant, author of six books focused on the environmental design of early childhood classrooms, and designer of two furniture collections called Sense of Place and Sense of Place for Wee Ones. She is eternally grateful for the many opportunities she has experienced to transform hundreds of ordinary early childhood environments into extraordinary, inspiring places for children to be, and become, their very best. | ||||

References

References

- University of Windsor. Uwindsor.ca

- Klepeis, N., Nelson, W., Ott, W., Robinson, J., Tsang, A., Switzer, P., Behar, J., Hern, S., & Engelmann, W. (2001). The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): A resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology, 11, 231-252.

- Velux America (2018). Needed: A Fresh Approach to Indoor Life. veluxusa.com

- deBrey, C., & Snyder, T. (February, 2021). Digest of Educational Statistics 2019. Institute of Education Statistics.

- Duncan, S., & Murray, K. (2021). Designing Brain-based Environments. Fairy Dust Teaching. Summer Conference.

- Epstein, A., & Hohmann, M. (2012). The HighScope Preschool Curriculum. Ypsilanti, Michigan: HighScope Press.

- Greenman, J. (2017). Caring Spaces, Learning Places. Children’s Environments that Work! Ed. Mike Lindstrom. Lincoln, Nebraska: Exchange Press.

- Bowes, J., Grace, R., & Hodge, K. (2012). Children, families, and communities: Contexts and consequences (4th ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press.

- Fisher, A., Goodwin, K., & Sellman, H. (2014). Visual Environment, Attention Allocation, and Learning in Young Children: When Too Much of a Good Thing May Be Bad. Psychological Science, 25(7), 1362-1370.

- Nagel, M., & Scholes, L. (2016). Understanding Development & Learning. Implications for Teaching. Victoria, Australia: Oxford University Press.

- Tokuhama-Espinosa, T. (2011). Mind, Brain, and Education Science. A Comprehensive Guide to the New Brain Based Teaching. New York, USA: Norton Books In Education.

- Elafifi, S., & Abdelaziz Farid, M.M. (2020). Architectural Design: Towards autism spectrum disorder wellbeing. International Journal of Engineering Research and Development. 16(12), pp 48-60.

- Nagel, M., & Scholes, L. (2016). Understanding Development & Learning. Implications for Teaching. Victoria, Australia: Oxford University Press.

- Harvard University. (2021). Centre on the developing child: Executive function and self regulation. Developingchild.harvard.edu

- Weinstein, C.S., & David, T.G. (1987). Spaces for Children: The Built Environment and Child Development. New York, New York: Plenum Press.

- World Health Organization (October, 2013). Combined or multiple exposure to health stressors in indoor built environments: An evidence-based review prepared for the WHO training workshop “Multiple environmental exposures and risks”. Edited by Dimosthenis A. Sarigiannis. euro.who.int

Tiffany Smith

Tiffany Smith