Using the Spatial Conditions of Emotions to design inspiring early childhood environments

by Sandra Duncan, EdD

Where are you . . . right now, this very moment?

Chances are, you are either in or very near a built environment. That’s because built environments are everywhere. They have been described as “surroundings created for humans, by humans, and to be used for human activity”.1

Built environments are the structures in which you live, work and play (i.e., homes, offices, movie theatres, factories, and shopping malls). Less considered and thought about built environments are vehicles and transportation systems such as highways and railways. Even if you are skiing down the groomed slopes of Colorado, bicycling in New York’s Central Park, or taking a walk on San Antonio’s River Walk, the sidewalks, pathways, or walkways are considered built environments. Unless you are living “off the grid”, there are – indeed – plenty of built environments surrounding you. Because built environments are everywhere, they have a powerful influence on our lives. One of the most important and influential built environments is the early childhood classroom.

Even the wood dock at your favourite fishing spot is a built environment

The importance of early childhood built environments

Young children spend an enormous amount of time in early childhood learning spaces. The 2019 Digest of Educational Statistics reported that children under the age of five who are in childcare centres spend an average of 30 hours a week in these built environments.2 With this statistic in mind, it is easy to understand why the indoor built environment is important and how it has the time and power to either positively or negatively shape the lives of young children.

Early childhood educators spend a great deal of thought, time, and energy designing and equipping their learning spaces. Educators are intentional about the furniture and the perfect place to put it. When making intentional decisions about the layout of their environments, for example, educators make sure that the right learning areas are included in the space. They make decisions about where to position these areas of play based on functionality. Positioning the art centre near a source of water and locating it on a tiled surface makes for easier clean-up. Or, placing the block centre in an isolated corner to reduce foot traffic and the possibility of children’s constructions being knocked over. In addition to the layout, early childhood educators also carefully select appropriate learning materials to include in each area of play.

While all this talk about designing a learning space based on functionality and filling the space with developmentally appropriate learning materials may sound familiar, there is actually a critical piece missing from our thinking. We are approaching the design of our learning spaces from a myopic rather than holistic perspective and end up with environments based on function rather than on young children’s emotional development. In their book, Child Development at the Intersection of Emotion and Cognition, researchers Calkins and Bell assert there is a significant link between intellect and emotions.3

“Emotion is the foundation of learning and must be the cornerstone of design for Early Childhood environments.” - Dr. Sandra Duncan

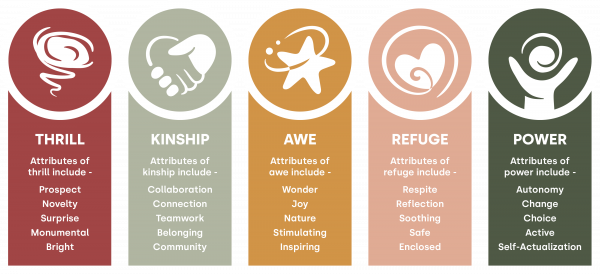

If emotions are at the cornerstone of cognition, then it becomes important for early childhood educators to consider children’s emotional responses to place (or our learning spaces). This goes beyond the traditional and old-fashioned conception of designing spaces for children. In addition to attending to functionality (i.e., where areas of play are located, what furniture we have, and how it is positioned), we must begin thinking about what Architect Faith Swickard calls Spatial Conditions of Emotion4. Swickard identified several emotional conditions that can be infused into the built environment. Some of these spatial conditions of emotion include (1) thrill; (2) kinship; (3) awe; (4) refuge; and, (5) power.

1. THRILL is the physiological condition of emotion

The spatial condition of thrill is easy to come by when working with young children. Simply create a long tunnel made out of cardboard boxes. It’s as if the end destination is going to change because children will crawl again….and again….and again. Just for the thrill of it.

2. KINSHIP is a spatial condition of emotion

The spatial condition of kinship in an early childhood environment is propagated by offering spaces conducive for children to connect with each other and with their space. This means that the environment provides affordances built for smaller groups to encourage sharing, cooperation, and collaboration. Humans are social beings — and children are no exception. Given the space and place to play or work together, children naturally gravitate towards each other.

Some strategies for spaces designed exclusively for two include - bench seats; a large ottoman; and a table for two.

3. AWE is a physiological condition of emotion

Awe is an emotion that has a powerful effect on our minds and bodies. Everyone — especially children — needs to feel the exhilaration and magic of the spatial condition of awe. Illumination, mirrors, prisms, and light and shadow experiences make a good beginning.

The Spatial Condition of awe is promoted when children are given opportunities to interact with wondrous objects such as a large unbreakable floor mirror coupled with LED lights and glittery metal balls.

4. REFUGE is a psychological condition of emotion

The spatial condition of refuge offers children the opportunity to recharge in a quiet, gentle way. If they are so inclined, they can grab a nearby book, puppet, or pillow and create the space all their own.

5. POWER is a behavioural condition of emotion

The spatial condition of power happens when educators hand over the reins of environmental control, giving children the power to create their own environments within their learning space.

Children’s memories are fueled by emotions. The stronger the emotional connection, the stronger the memory. When a child has grown into adulthood, they will not remember the table or chair—what it was made from, what colour it was, or how it looked. What they will remember is what was built and how it made them feel. Activating the spatial condition of power taps into the emotions area of the brain and is important for children’s long and short-term memories. Power-centred environments invite children to act upon and change the learning spaces architecture.

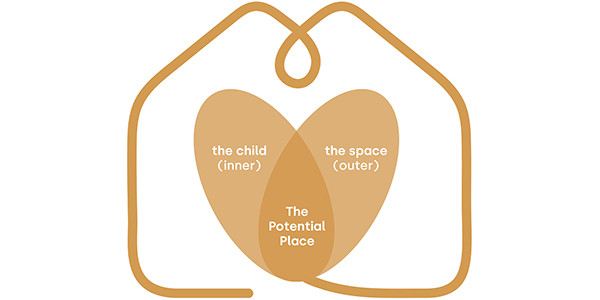

Although we pay enormous attention to the quantitative aspects of our learning space, we sometimes overlook the importance of the child’s inner space or the emotional connection. This oversight may be because inner space is hard to quantify — it’s hard to measure and difficult to count. This oversight could be a result of mandated environmental rating scales, which primarily rate through observation of visible objects (i.e., the number of blocks) rather than emotions. Perhaps considering the spatial conditions of emotions in a learning space never occurred to you until now.

Consider how to infuse the spatial conditions of emotions into the learning space. When you do this, you are actually designing at the intersection of the child (inner) and the environment (outer). Discovering what might be helpful in designing for emotions — for the qualitative side of the equation — for the spatial conditions of emotion.

![]()

References:

1. University of Windsor. https://www.uwindsor.ca/vabe/25/what-does-term-“built-environment”-mean

2. deBrey, C. & Snyder, T. (February, 2021). Digest of Educational Statistics 2019. Institute of Education Statistics.

3. Calkins & Bell (2010). Child Development at the Intersection of Emotions and Cognition.

4. Faith Swikard (2018). https://www.faithswickard.com/spatial-conditions-of-emotion

Sandra Duncan

Sandra Duncan

Tiffany Smith

Tiffany Smith